By: Alusine Rehme Wilson

Since President Julius Maada Bio launched the Free Quality Education Project (FQEP) in 2018, the initiative has aimed to remove financial barriers to schooling for children across Sierra Leone. But in recent years, a recurring controversy has raised doubts about just how “free” this education really is.

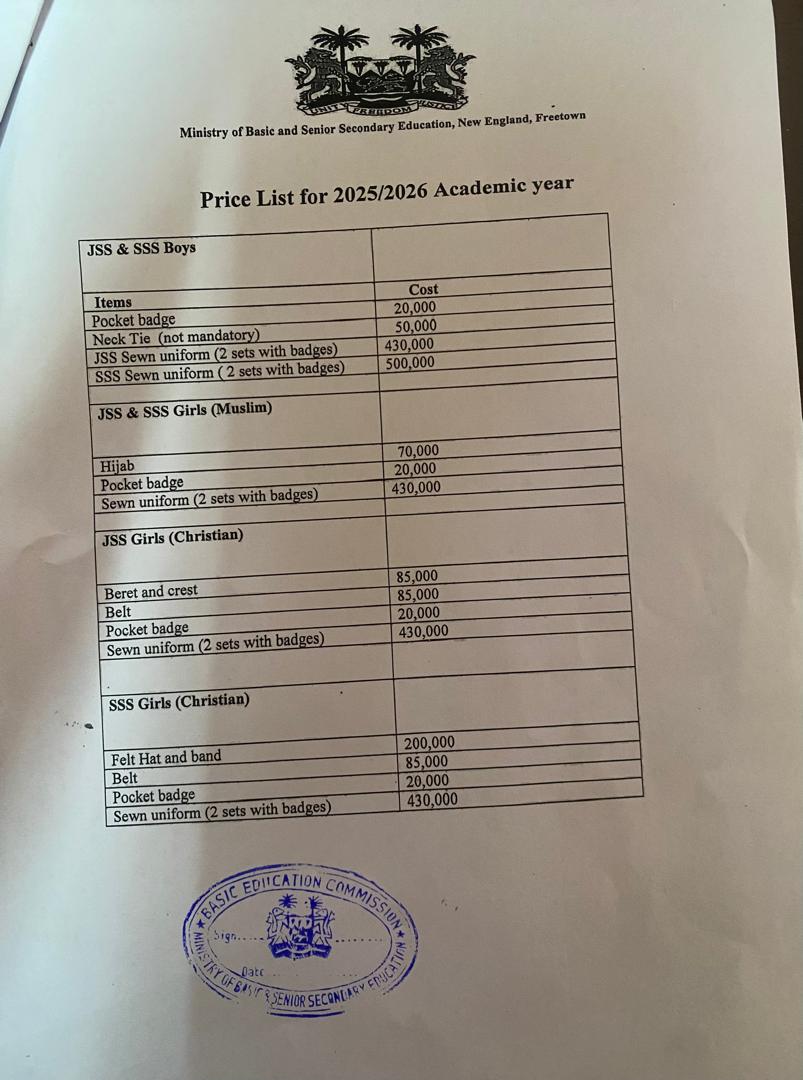

Every year, starting with the 2021/2022 academic session, the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary School Education (MBSSE), in partnership with school administrators, releases a price list for items required for pupils entering Junior Secondary School 1 (JSS-1) and Senior Secondary School 1 (SSS-1). These include uniforms, belts, crests, neckties, and other school-branded materials.

While the government continues to cover tuition fees, parents are still required to pay for these items, prompting concerns about the real cost of free education. Many parents argue that the cost of admission materials has become a significant burden, especially for those in rural areas with unstable incomes.

In cities like Makeni and Bo, as well as rural towns and villages, public dissatisfaction is growing. Critics say the annual price lists for school items are undermining the very goals of the FQEP.

Mr. Alieu Bangura, an English teacher and school administrator in Makeni, supports the vision behind the FQEP but highlights key flaws. He warns that many families, especially in remote communities, simply can’t afford the admission costs.

“These are tough times,” Bangura says. “For the average unemployed Sierra Leonean, raising NLe 100 a week is nearly impossible. If the government doesn't step in to clarify admission conditions and raise awareness, we’ll see more school dropouts.”

Mrs. Isatu Barrie, a primary school teacher in Bo, also criticized the policy. She told AWE Media Sierra Leone that requiring parents to pay for admission items contradicts the principle of free education.

“MBSSE should focus on paying outstanding school subsidies instead of asking parents to pay for items that should be free under the FQEP,” she said.

Similarly, other teachers and school heads across the country echoed these concerns. They argue that the government’s failure to pay school subsidies, especially for the second and third terms of the last academic year, has forced schools to push costs onto parents.

This has raised suspicions that school heads may be profiting from these mandatory admission sales, while parents shoulder the financial weight. Some parents even say they're paying more for school items now than before the Free Quality Education initiative began.

Despite the backlash, the MBSSE defends the annual price list policy. They argue that standardizing prices helps prevent exploitation and ensures fairness.

“Before the FQEP, school admissions were difficult and expensive for ordinary families,” an MBSSE statement said. “Now we’re putting regulatory mechanisms in place so that prices are controlled and fair.”

The Ministry has issued guidelines requiring all schools to: clearly display the price list on their notice boards, include MBSSE representatives in admission committees, and, allow parents to buy items from outside vendors if they prefer.

They also insist that the purchase of admission items should not be a requirement for enrollment and have encouraged parents to report any violations via the toll-free line 8060.

While the intentions of the Free Quality Education Project remain noble, its implementation raises serious questions. If education is truly free, why are so many families still paying out of pocket just to get their children into school?

Until these concerns are addressed, and the burden on parents eased, many will continue to ask: Who really benefits from these annual school item price lists, the public, or the system?

Comments

Post a Comment